This Day In History

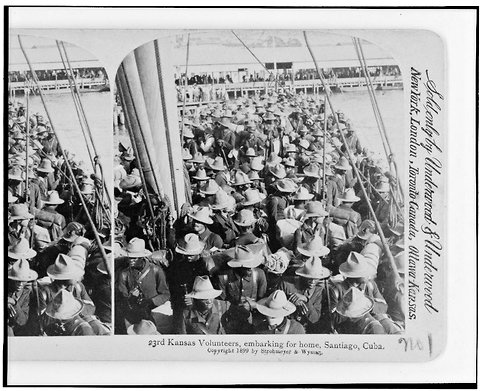

1898 Armistice ends the Spanish-American War

The brief and one-sided Spanish-American War comes to an end when Spain formally agrees to a peace protocol on U.S. terms: the cession of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Manila in the Philippines to the United States pending a final peace treaty.

The Spanish-American War had its origins in the rebellion against Spanish rule that began in Cuba in 1895. The repressive measures that Spain took to suppress the guerrilla war, such as herding Cuba’s rural population into disease-ridden garrison towns, were graphically portrayed in U.S. newspapers and enflamed public opinion. In January 1898, violence in Havana led U.S. authorities to order the battleship USS Maine to the city’s port to protect American citizens. On February 15, a massive explosion of unknown origin sank the Maine in the Havana harbor, killing 260 of the 400 American crewmembers aboard. An official U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry ruled in March, without much evidence, that the ship was blown up by a mine but did not directly place the blame on Spain. Much of Congress and a majority of the American public expressed little doubt that Spain was responsible, and called for a declaration of war.

In April, the U.S. Congress prepared for war, adopting joint congressional resolutions demanding a Spanish withdrawal from Cuba and authorizing President William McKinley to use force. On April 23, President McKinley asked for 125,000 volunteers to fight against Spain. The next day, Spain issued a declaration of war. The United States declared war on April 25. On May 1, the U.S. Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey destroyed the Spanish Pacific fleet at Manila Bay in the first battle of the Spanish-American War. Dewey’s decisive victory cleared the way for the U.S. occupation of Manila in August and the eventual transfer of the Philippines from Spanish to American control.

On the other side of the world, a Spanish fleet docked in Cuba’s Santiago harbor in May after racing across the Atlantic from Spain. A superior U.S. naval force arrived soon after and blockaded the harbor entrance. In June, the U.S. Army Fifth Corps landed in Cuba with the aim of marching to Santiago and launching a coordinated land and sea assault on the Spanish stronghold. Included among the U.S. ground troops were the Theodore Roosevelt-led “Rough Riders,” a collection of Western cowboys and Eastern blue bloods officially known as the First U.S. Voluntary Cavalry. On July 1, the Americans won the Battle of San Juan Hill, and the next day they began a siege of Santiago. On July 3, the Spanish fleet was destroyed off Santiago by U.S. warships under Admiral William Sampson, and on July 17 the Spanish surrendered the city–and thus Cuba–to the Americans.

In Puerto Rico, Spanish forces likewise crumbled in the face of superior U.S. forces, and on August 12 an armistice was signed between Spain and the United States. On December 10, the Treaty of Paris officially ended the Spanish-American War. The once-proud Spanish empire was virtually dissolved, and the United States gained its first overseas empire. Puerto Rico and Guam were ceded to the United States, the Philippines were bought for $20 million, and Cuba became a U.S. protectorate. Philippine insurgents who fought against Spanish rule during the war immediately turned their guns against the new occupiers, and 10 times more U.S. troops died suppressing the Philippines than in defeating Spain.

Source: www.history.com

This Day In History

Truman announces development of H-bomb

U.S. President Harry S. Truman publicly announces his decision to support the development of the hydrogen bomb, a weapon theorized to be hundreds of times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan during World War II.

Five months earlier, the United States had lost its nuclear supremacy when the Soviet Union successfully detonated an atomic bomb at their test site in Kazakhstan. Then, several weeks after that, British and U.S. intelligence came to the staggering conclusion that German-born Klaus Fuchs, a top-ranking scientist in the U.S. nuclear program, was a spy for the Soviet Union. These two events, and the fact that the Soviets now knew everything that the Americans did about how to build a hydrogen bomb, led Truman to approve massive funding for the superpower race to complete the world’s first “superbomb,” as he described it in his public announcement on January 31.

On November 1, 1952, the United States successfully detonated “Mike,” the world’s first hydrogen bomb, on the Eniwetok Atoll in the Pacific Marshall Islands. The 10.4-megaton thermonuclear device, built upon the Teller-Ulam principles of staged radiation implosion, instantly vaporized an entire island and left behind a crater more than a mile wide. The incredible explosive force of Mike was also apparent from the sheer magnitude of its mushroom cloud–within 90 seconds the mushroom cloud climbed to 57,000 feet and entered the stratosphere. One minute later, it reached 108,000 feet, eventually stabilizing at a ceiling of 120,000 feet. Half an hour after the test, the mushroom stretched 60 miles across, with the base of the head joining the stem at 45,000 feet.

Three years later, on November 22, 1955, the Soviet Union detonated its first hydrogen bomb on the same principle of radiation implosion. Both superpowers were now in possession of the “hell bomb,” as it was known by many Americans, and the world lived under the threat of thermonuclear war for the first time in history.

Source: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/truman-announces-development-of-h-bomb

This Day In History

Gandhi assassinated

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the political and spiritual leader of the Indian independence movement, is assassinated in New Delhi by a Hindu extremist.

Born the son of an Indian official in 1869, Gandhi’s Vaishnava mother was deeply religious and early on exposed her son to Jainism, a morally rigorous Indian religion that advocated nonviolence. Gandhi was an unremarkable student but in 1888 was given an opportunity to study law in England. In 1891, he returned to India, but failing to find regular legal work he accepted in 1893 a one-year contract in South Africa.

Settling in Natal, he was subjected to racism and South African laws that restricted the rights of Indian laborers. Gandhi later recalled one such incident, in which he was removed from a first-class railway compartment and thrown off a train, as his moment of truth. From thereon, he decided to fight injustice and defend his rights as an Indian and a man. When his contract expired, he spontaneously decided to remain in South Africa and launched a campaign against legislation that would deprive Indians of the right to vote. He formed the Natal Indian Congress and drew international attention to the plight of Indians in South Africa. In 1906, the Transvaal government sought to further restrict the rights of Indians, and Gandhi organized his first campaign of satyagraha, or mass civil disobedience. After seven years of protest, he negotiated a compromise agreement with the South African government.

In 1914, Gandhi returned to India and lived a life of abstinence and spirituality on the periphery of Indian politics. He supported Britain in the First World War but in 1919 launched a new satyagraha in protest of Britain’s mandatory military draft of Indians. Hundreds of thousands answered his call to protest, and by 1920 he was leader of the Indian movement for independence. He reorganized the Indian National Congress as a political force and launched a massive boycott of British goods, services, and institutions in India. Then, in 1922, he abruptly called off the satyagraha when violence erupted. One month later, he was arrested by the British authorities for sedition, found guilty, and imprisoned.

Source: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/gandhi-assassinated

This Day In History

U.S. Baseball Hall of Fame elects first members

On January 29, 1936, the U.S. Baseball Hall of Fame elects its first members in Cooperstown, New York: Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Matthewson and Walter Johnson.

The Hall of Fame actually had its beginnings in 1935, when plans were made to build a museum devoted to baseball and its 100-year history. A private organization based in Cooperstown called the Clark Foundation thought that establishing the Baseball Hall of Fame in their city would help to reinvigorate the area’s Depression-ravaged economy by attracting tourists. To help sell the idea, the foundation advanced the idea that U.S. Civil War hero Abner Doubleday invented baseball in Cooperstown. The story proved to be phony, but baseball officials, eager to capitalize on the marketing and publicity potential of a museum to honor the game’s greats, gave their support to the project anyway.

In preparation for the dedication of the Hall of Fame in 1939—thought by many to be the centennial of baseball—the Baseball Writers’ Association of America chose the five greatest superstars of the game as the first class to be inducted: Ty Cobb was the most productive hitter in history; Babe Ruth was both an ace pitcher and the greatest home-run hitter to play the game; Honus Wagner was a versatile star shortstop and batting champion; Christy Matthewson had more wins than any pitcher in National League history; and Walter Johnson was considered one of the most powerful pitchers to ever have taken the mound.

Today, with approximately 350,000 visitors per year, the Hall of Fame continues to be the hub of all things baseball.

Source: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/u-s-baseball-hall-of-fame-elects-first-members

-

NEWS1 year ago

NEWS1 year ago2 hurt, 1 jailed after shooting incident north of Nocona

-

NEWS5 months ago

NEWS5 months agoSuspect indicted, jailed in Tia Hutson murder

-

NEWS1 year ago

NEWS1 year agoSO investigating possible murder/suicide

-

NEWS1 year ago

NEWS1 year agoWreck takes the life of BHS teen, 16

-

NEWS9 months ago

NEWS9 months agoMurder unsolved – 1 year later Tia Hutson’s family angry, frustrated with no arrest

-

NEWS12 months ago

NEWS12 months agoSheriff’s office called out to infant’s death

-

NEWS1 year ago

NEWS1 year agoBowie Police face three-hour standoff after possible domestic fight

-

NEWS1 year ago

NEWS1 year agoDriver stopped by a man running into the street, robbed at knifepoint